My grandfather, Yurij Fojczuk, immigrated to Canada in April 1913 at the age of 17 from Verenchanka, in what’s now Ukraine, but at that time it was under Austro-Hungarian rule.

Life was not good for people like the Yurij, his sister, and widowed mother. They worked most of each week without pay for the church and the landowner with little time (or land) of their own. Family circumstances would get even worse for the family once Yurij was drafted into the Austrian army and there were only two people to do all the work.

Yurij saw a Canadian advertisement promising 160 acres of prime farmland for a nominal fee. Yurij decided that the only way his family could survive would be for him to come to Canada before he was drafted. He would then save enough money to bring his sister and mother to Canada.

Yurij received that 160 acres of prime land in the Willingdon area of Alberta, but that land was covered with thousands of trees. He cleared as much land as he could all spring and summer, and then over the winter of 1913-1914 he worked in coal mines, saving as much money as he could. By August 1914, he bundled up all that he had saved and sent it to his mother, but by sad coincidence, World War I was just declared. His mother never got the money, nor was the packet ever returned to him.

To make matters worse, Yurij suddenly became an enemy of his adopted country. Canada was at war with the Austro-Hungarian Empire and even though Yurij was Ukrainian, he was considered an Austrian.

Yurij had to carry his identity papers with him and he was required to have them stamped regularly by the police. But one day when he went to get his papers stamped, he was arrested instead. This was in 1915.

A hundred years after the fact it’s hard to know exactly why he was arrested. He hadn’t broken any law and had dutifully kept his papers up to date. But he was a strong man, and single, and the government had heavy labour that needed to be done.

Yurij was imprisoned in various internment camps in the Rockies but by 1916 he ended up at the Jasper Internment Camp. The conditions were brutal and he was required to work, in his words, “from dark to dark” with armed guards patrolling. One thing he learned to do was to run while carrying a log on his shoulder.

Frostbite, injuries, and brutal working conditions forced Yurij to make a drastic decision. In 1917, he felt that if he stayed any longer as a prisoner that he would die. So he waited for his chance and ran off in the cover of night. Guards shot at him and he felt the bullets whizzing by his ears, but he escaped.

He hid out in the woods and eventually made his way to the Lethbridge and Coleman area where there was a coal mining town. He changed his name to George Forchuk and got a job.

In 1918, he was sitting in a restaurant with a friend. A policeman told him he was in trouble. George thought he was caught as an escapee of Jasper Internment Camp. “The war’s over,” said the policeman. “No one cares about your escape. You’re in trouble for not wearing a mask.”

This was during the Spanish Flu epidemic and people were fined a dollar for not wearing a mask. George paid the dollar. He went back to his homestead Willingdon, but it was no longer his. The government had given it to an English family.

His Ukrainian neighbours were standoffish, thinking that he must be a criminal seeing as he had been in an internment camp. He left the area, devastated.

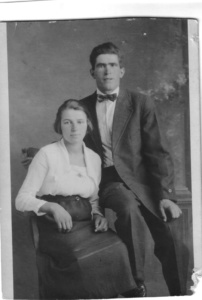

He applied for a new homestead, but by this time all of the good land had been parceled out. He ended up with marginal land between Myrnam and Lake Eliza. He married in his late 20s, and he and Anna raised three sons and two daughters (two other children died in infancy). They ran a ferry across the North Saskatchewan River, and in the winter George would work in the coal mines again, leaving Anna to manage the farm and the five kids. In time they saved enough money to buy a homestead in Innisfree, Alberta, and the land on this third homestead was nearly of the quality of that first one in Willington, that he lost at age seventeen.

During all of this time, George tried to contact his family in Verenchanka but was unsuccessful.

George found out in bits and pieces from new immigrants from his region that his mother and sister had not fared well. Their village was in the fighting zone during the First World War and after that, their region was taken over first by Romania, then by the Soviet Union. During all of this upheaval, communication between George and his mother and sister was nearly impossible.

After WWII, George did get news of his family. His sister was dead. She had joined the Ukrainian Insurgent Army to fight for Ukraine’s independence. She was shot and killed by the Soviets and buried in a mass grave. George’s mother was punished for her daughter’s patriotism by being exiled to Siberia, where she died.