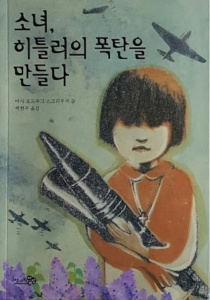

In this companion book to the award-winning Stolen Child, a young girl is forced into slave labour in a munitions factory in Nazi Germany. In Stolen Child, Marsha Forchuk Skrypuch introduced readers to Larissa, a victim of Hitler’s largely unknown Lebensborn program. In this companion novel, readers will learn the fate of Lida, her sister, who was also kidnapped by the Germans and forced into slave labour — an Ostarbeiter.

In addition to her other tasks, Lida’s small hands make her the perfect candidate to handle delicate munitions work, so she is sent to a factory that makes bombs. The gruelling work and conditions leave her severely malnourished and emotionally traumatized, but overriding all of this is her concern and determination to find out what happened to her vulnerable younger sister.

With rumours of the Allies turning the tide in the war, Lida and her friends conspire to sabotage the bombs to help block the Nazis’ war effort. When her work camp is finally liberated, she is able to begin her search to learn the fate of her sister.

In this exceptional novel Marsha Forchuk Skrypuch delivers a powerful story of hope and courage in the face of incredible odds.

Excerpt:

Chapter One

1943

Losing Larissa

The room smelled of soap and the light was so white that it made my eyes ache. I held Larissa’s hand in a tight grip. I was her older sister after all, and she was my responsibility. It would be easy to lose her in this sea of children, and we had both lost far too much already. Larissa looked up at me and I saw her lips move but I couldn’t hear her words above the wails and screams. I bent down so that my ear was level with her lips.

“Don’t leave me,” she said.

I wrapped my arms around her and gently rocked her back and forth. I whispered our favourite lullaby into her ear.

A loud crack startled us both. The room was suddenly silent. A woman in white stepped in among us. She clapped her hands sharply once more.

“Children,” she said in brisk German. “You will each have a medical examination.”

Weeping children were shoved into a long snaking line that took up most of the room. I watched as one by one other children were taken behind a broad white curtain.

When it was Larissa’s turn her eyes went round with fright. I did not want to let go of her, but the nurse pulled our hands apart.

“Lida, stay with me!”

I stood at the edge of the curtain and watched as the woman made Larissa take off her nightgown. My sister’s face was red with shame. When the woman held a metal instrument to her face, Larissa screamed. I rushed up and tried to knock that thing out of the nurse’s hand, but she called for help and someone held me back. When they finished with Larissa, they told her to stand at the other end of the room.

When it was my turn, I barely noticed what they were doing. I kept my eyes fixed on Larissa. She was standing with three other children. Dozens more had been ordered to stand in a different spot.

When the nurse was finished with me, I slipped my nightgown back on. I was ordered to stand with the larger group – not with Larissa’s.

“I need to be in that group,” I told the nurse, pointing to where Larissa stood, her arms out-stretched, a look of panic on her face.

The nurse’s lips formed a thin flat line. “No talking.”

She put one hand on each of my shoulders and shoved me toward the larger group. A door opened wide. We were herded out into the blackness of night.

Larissa screamed, “Lida! Don’t leave me!”

I looked back into the room, but could not see her. “I will find you, Larissa!” I shouted. “I promise. Stay strong.”

A sharp slap across my face sent me sprawling onto the cold wet grass. I scrambled up and tried to break through the sea of children. I had to get back to Larissa. Strong arms wrapped around my torso and lifted me up. I was thrown into blackness. With a screech of metal the door slammed shut.

Reviews

Reviews:Michal Hoschlander Malen on Jewish Book Council wrote:

Lida and her sister, Larissa, kidnapped from their Ukrainian village by the Nazis in 1943, are separated in the first chapter of this powerful wartime story and the book follows older sister Lida as she worries about Larissa and tries to survive the horrors of a slave labor camp. She is aware of the plight of the Jews; her mother had tried to save a Jewish girl and had been shot for it and one of her fellow inmates is also Jewish, unbeknownst to their captors. Both girls know that that discovery of this fact will lead to immediate death. The situation of prisoners like Lida was not, of course, the same as that of Jews in concentration camps but it was harsh and terrifying and this piece of history is not widely known. One of Lida’s main tasks was the assembling of bombs for the use of the German war effort and she makes an effort to sabotage as many bombs as she can. Somehow Lida manages to survive and is reunited with her sister whose story is told in a companion volume, Stolen Child. This book is gritty, raw and excellently written and tells the story in a memorable way. It is recommended for ages 9-14.

Fern Folio on http://fernfolio.edublogs.org/2014/01/29/making-bombs-for-hitler-by-marsha-forchuk-skrypuch/ wrote:

Written by Marsha Forchuk Skrypuch and winner of the 2013 Silver Birch Fiction prize, Making Bombs for Hitler is the poignant and chilling and deeply moving account of a young Ukrainian girl’s experiences working as a slave labourer in Nazi Germany. Filled with instances of shocking inhumanity and calculated cruelty, and small and great acts of courage and kindness, this story will move you to tears. A wonderful book for readers from Grade 5.

Christina Minaki on Children’s Book News wrote:

From Canadian Children’s Book News, Summer 2012: With Making Bombs For Hitler, author Marsha Skrypuch continues the story of two sisters, Lida and Larissa, that she began with Stolen Child.

Making Bombs for Hitler is Lida’s story. Lida’s morther had said it was possible to find beauty anywhere, but she — like Lida’s father and grandmother — was killed before her daughters were captured by the Germans. Beauty is almost impossible to find in a brutal Nazi slave labour camp. But Lida’s strongest motivation to survive is her quest to find her beloved sister, Larissa.

Lida knows she needs to remain useful in the camp if she is to survive — and death can happen at any time. Doctors and nurses will kill those deemed “unfit” to be a part of the Nazis “machine.” Guards can barely wait for an excuse to berate, brutalize or kill their prisoners. There is the gnaw of hunger and the reality of misery and torture everywhere. Then Lida and some of her friends are given a new work assignment: making bombs — a task they have no choice but to undertake. It is a blessing that by now she knows there is beauty, even in the camp — in a shared song or story, a loving memory, a selfless act of resistance.

These gifts sustain her, both as a prisoner, and later, in a refugee camp, where she is finally safe. All she has to do is somehow find dear Larissa and a way back home. But finding Larissa will take nothing short of a miracle. And if the rumours about Ukraine are true, going home may never happen.

Making Bombs for Hitler is an achingly sad and intensely hopeful novel — honest about suffering, but also about resilience. It is gripping in its plot and its striking characters, and full of historical accuracy.

In Stolen Child, it takes Larissa almost the entire novel to remember her real name and her past. She spent five years in a Displaced Persons camp with the loving couple who have brought her to Brantford, Ontario. She knows that she must refer to Marusia and Ivan as her mother and father or they will risk losing their place in Canada. She must also go by the name Nadia. But disturbing, disjointed flashbacks and nightmares are raising troubling questions.

Why are her happy memories infused with the colour and scent of lilacs? Why are her horrible memories tied to blood and flames and desperate cries? Who are her real mother and sister? And why is she almost certain the boys who call her a Nazi are right?

Stolen Child brilliantly and deftly deals with the horrifying issues of post-traumatic stress disorder and the Lebensborn program (the Nazis stole blond, blue-eyes Polish and Ukrainian children and brainwashed them before placing them with their ‘rightful’ Nazi families). Larissa became one such child, and the road back to the truth is terrifying. She must have courage if she is ever to have peace or find Lida.

When, at the end of Making Bombs For Hitler, Lida is finally given a letter from Larissa, a beautiful link is made between Making Bombs for Hitler and Stolen Child. These two novels are a perfect fit, covering not only war, prejudice, injustice and loss, but also love, healing and new beginnings.

Enrolled in the Humber College Creative Writing Program, Christina Minaki is working on her second novel.

Roxanne Burton on Resource Links wrote:

Rating: Excellent, enduring, everyone should see it!

SKRYPUCH, Marsha Forchuk Making Bombs for Hitler

Scholastic Canada, 2012. 186p. Gr. 4 – up. 978-1-44310730-3. Pbk. $8.99

Making Bombs for Hitler is a companion novel to Marsha Forchuk Skrypuch’s previous novel. Stolen Child This novel tells the story of Lida, a young Ukrainian girl who lost her parents during World War II, and who, with her sister, is taken away from her grandparent’s care by the Nazis and sent to a forced work camp. Before arriving at their final destination, the girls are separated, and Lida must do all she can to survive the conditions of deprivation and despair in the camp, clinging to the hope that one day she will be reunited with her sister.

This novel really tells two stories. On the surface, it is the story of Lida, and how she triumphs over adversity by being resourceful and optimistic, even in the face of cruelty and sadness. Lida emerges as a leader, through her compassion towards other camp workers, and by her bravery in helping to sabotage the bombs that she and the other workers are forced to manufacture for the Nazis. Her example brings courage and hope to those with whom she is imprisoned; she demonstrates empathy and humanity in the most brutal conditions, even when the adults around her treat her as though she is less than human. The novel also tells a parallel story, that of the Ostarbeiter, or East Workers. Beginning in 1943, an estimated 3 million to 5.5 million people, mostly under the age of 25, were abducted from the area of Reichskom- missariat, Ukraine by the Nazis. They were used as forced laborers, with the law enabling the Nazis to use these prisoners until they died from overwork, malnutrition, and exposure. After the war ended and the prisoners were repatriated to the Soviet Union, many were sent to work camps in Siberia or killed by their own government, as Stalin viewed these former Nazi prisoners as Nazis themselves.

This novel contains some stark and unsettling descriptions of conditions in forced work camps and the way in which prisoners were treated as expendable commodities, rather than human beings. Parents and educators may wish to use sections of the novel as a starting point for discussions about some of the events of World War II and how these events have impacted our laws today.

Thematic Links: World War 1939-1945 Children; World War 1939-1945- Prisoners and Prisons; Sisters

Roxanne Burton

Helen Kubiw on Canlit For Little Canadians wrote:

From Helen Kubiw: The title of Marsha Skrypuch’s newest book may blindside you, even knock you senseless about reading it, but it would be a shame for anyone not to read this compassionate historical fiction about a little known tragedy of World War II. As always, Skrypuch demonstrates that she is to be trusted and respected for her ability to transform even horrific history into gentle but honest and enlightening stories.

With Russian Communist rule in Ukraine and Stalin determined to destroy the country to keep it from the Germans coupled with the Nazis heading for Moscow by invading Ukraine, Ukrainians were in an unfortunate position, territorially and psychologically, during World War II. Sadly, this senseless situation leads to the murder of eight-year-old Lida Ferezuk’s father by the Russians and her mother by the Nazis. Separated from her younger sister, Larissa, Lida is taken with numerous Ukrainian children to Germany to be Ostarbeiter (eastern workers) for the Nazis.

Housed in barracked camps, provided with no clothes or shoes, and essentially starved on watery broth once a day, Lida and other children are slave workers for the Nazis, kept only as long as they are useful. After showing her skills with needle and thread, Lida is assigned to the Nazi laundry. But, after being gifted a cast-off shirt by the laundress, Officer Schmidt decides Lida has been too privileged and assigns her with five others girls to construct bombs in a compound away from the camp.

With repeated defeats at the front, many Nazis retreat and, without supervision, the girls begin to sabotage the bombs to ensure they are ineffective. But, relentless bombing by the Allies destroys the camp, allowing many to escape. Unfortunately, a number of them, including Lida, are captured and taken to a German town where their enslavement is reimposed under a man manufacturing ammunition. Locked in a basement, they endure inhumane conditions, worsened when they are abandoned by the departing Germans feeling the threat of the Allied forces.

The inevitable arrival of Allied soldiers and their discovery of Lida and others brings the reader small pleasure, as the deaths of many and the images of the starved with legs turning to sticks and teeth loosening cannot be erased or ameliorated. Even with their rescue and care by compassionate soldiers and nurses, the Ukrainian children are in jeopardy from the Soviets who view them as Nazis, deserving of punishment. If they do survive the machinations of the Soviets to retrieve and punish them, many will spend years in displaced persons camps, waiting, hoping to be reunited with family.

This heart-breaking story, as told from Lida’s young eyes and heart, offers an opportunity for our young readers to get a different perspective of World War II beyond the battles expounded upon in history books or Remembrance Day activities at school or the tragedy of the Jewish people. It provides an opportunity to see war from a Ukrainian child’s perspective, hopefully sparking discussions with grandparents or research to understand more fully the plight of so many during war. [n.b. I may begin my own research with A History of Ukraine by Paul R. Magocsi (University of Toronto Press, 1996)]

Being of Ukrainian heritage, recalling vague discussions about Ukrainians dealing with the enemy they knew and the enemy they didn’t, I recognize that choices were more akin to gambles, made with the single goal of survival. As Lida acknowledges, even with the difficulty in believing that people could be so cruel, they saw hope even when there was none, just as Lida tries to see beauty anywhere, just as her mother deemed it was possible. Helen Kubiw, Canlit for Little Canadians.

Walter Kish on New Pathway wrote:

From Volodomyr Kish: Marsha Skrypuch certainly needs no introduction either to the Ukrainian community in Canada or to this country’s literary scene in general. As one of Canada’s foremost writers of books for children and young adults, she has earned numerous awards and distinctions for her prolific output.

Making Bombs for Hitler is her fifteenth book, and like many of her previous works, it deals with the painful and tragic effects of war and historical turmoil upon innocent victims. In this case, it portrays the experiences of Lida Ferezuk, a young Ukrainian girl not even in her teens, who is uprooted from everything she has known and held dear by the German invasion of Ukraine during the Second World War. Like millions of other young Ukrainian people, she is taken into forced labour in Germany where she joins the ranks of the Ostarbeiter, in effect, slave labourers from the East. The Germans considered Ostarbeiter to be Untermensch or sub-human. As such, they were used, abused and often literally worked to death, keeping the Nazi war machine going.

The story traces Lida’s agonizing experiences as she is orphaned and taken from her home to eventually wind up working in a small factory making bombs for the German military, hence the book’s title. Her struggle to survive in the face of overwhelming trials and tribulations is painted in vivid and yet at the same time very human terms. Skrypuch possesses a unique and distinctive ability of being able to place the reader into a protagonist’s consciousness, so that we experience and feel what the story’s main character sees and feels. It makes for a gripping read. Despite the fact that the book is geared for a young adult audience, once I started reading, I did not put the book down until I had finished it. It was that captivating.

Although the story is ostensibly fictional, it is based on real accounts, and the experiences described are historically accurate. It is estimated that some 2.5 million young Ukrainians were taken as Ostarbeiter to work in Germany. A significant number died from hunger, disease, overwork and as innocent victims of bombings or being caught in the crossfire of battling armies. After the war, most were forcibly repatriated to the Soviet Union where they were unjustly subjected to retribution and persecution by the Communists as being “collaborators” and “traitors”. A small number were able to immigrate to new homes in Western Europe, North America, Australia, as well as other countries.

The story has a personal resonance in that my mother and one of my uncles who did manage to reach Canada after the war were Ostarbeiter. While they were still alive, I tried a number of times to get them to recount the details of their experiences in Germany during the war. Regrettably, they were more than a little reluctant to speak of that cruel period in their young lives. I was usually rebuffed with a statement to the effect that it was better that I did not know of the inhumanity and cruelty that people were capable of inflicting They wanted to put that sad time behind them.

As much as I can understand their unwillingness to resurrect painful memories, I think that it is vitally important for posterity that their story be told. Sadly, too little has been written of this shameful history and the world is too little aware of the human toll that it took on Ukraine and Ukrainians.

There have been a number of attempts in recent decades by scholarly researchers in Canada to document the experiences of Ukrainians who lived through these events and wound up immigrating to Canada from the DP (Displaced Persons) camps after the war. Sadly, these efforts gained little traction, as most people, similar to my mother, were unwilling to confront the psychological scars that those times had inflicted on their psyches.

I am glad that Skrypuch decided to shine a moving and interesting spotlight on these events within her historical narrative. Regardless of one’s age, it is a book well worth reading. Published by Scholastic Canada Ltd, it will be available in bookstores across Canada as of February 1, as well through Amazon.ca.

From Rebecca’s Book Blog: This book tells the story of Lida, a fictional young Ukranian girl, who is captured by the Nazis to be used for slave labor shortly before her ninth birthday. Lida’s father was killed by the Soviets, and her mother was shot by the Nazis for attempting to hide their Jewish neighbors. After that, Lida and her beloved younger sister, Larissa, went to live with their grandmother, where they were captured by the Nazis. The girls were separated, with Lida being sent to a work camp. Lida is devastated, as she doesn’t know what happened to her sister, her only remaining family, and she fears she might have been harmed or killed because she is too young to work.

The conditions at the work camp are awful. Lida lies about her age, hoping she will be seen as more useful, and thus, be kept alive. There is never enough food and everyone is cold and hungry. Lida is lucky, because she is given a good position working in the laundry, which is clean and warm. However, after a few months, she is forced to go to work in a factory, making bombs for the Nazis. Lida hates having to help the Nazi war effort, because if they win, she will never be free again. However, she is able to find comfort from memories of her family, from her friendship with other children living at the camp, and from keeping alive her hope that one day she will find her sister again.

Before reading Making Bombs for Hitler, I didn’t know that so many children and young adults from Eastern Europe had been used as slave labor by the Nazis during World War II. I wouldn’t necessarily say I enjoyed reading this book, because it’s a very sad and tragic story about the suffering of children in war. However, I think it is a very important story to tell, and the author tells it well. Lida was a very couragous character who survived living and working in conditions that were nearly unbearable, all the while keeping alive the hope that she would someday be reunited with her sister. This book is a companion novel to another book by the author, Stolen Child, which was about Lida’s sister, Larissa. Making Bombs for Hitler can be read as a standalone, but you will want to read Stolen Child too, to find out how Larissa survived the war. I recommend this book to young readers studying World War II as well as to adults with an interest in the subject.

Rebecca’s Book Blog.

on Montreal Gazette:

In Making Bombs for Hitler, a Ukrainian woman warns 8-year-old Lida in the cattle car transporting her to slavery in Germany, “Be useful or they will kill you.”

Lida’s story dramatizes the little-known story of slave raids made by Nazi forces in the Soviet Union during the war. Young people were rounded up and used for forced labour in appalling conditions. Many were worked or starved to death; some were used in medical experiments.

From the Bukovina region of Ukraine, Lida is all alone in the world. Her mother was murdered by Nazis as she tried to help Jews, her father was killed by the Soviets. Lida is ripped away from her younger sister, whose story is told in the earlier novel, Stolen Child.

Lida learns to lie to protect herself, to say she is much older than she looks. But, alongside shrewdness, she has other sources of strength. She remembers her mother’s teaching that “You can make beauty anywhere.” And so she takes pains to stitch her work badge, the one that marks her in the eyes of her masters as a subhuman from Ukraine. Her talent with a needle saves her on more than one occasion, but her survival instinct doesn’t blunt her conscience. In a brave attempt to shield a Jewish child, she gives up her one precious keepsake, an iron crucifix.

Making Bombs for Hitler is a sensitively written page turner that teaches lessons in courage, faith, ingenuity and hard work. Lida’s odyssey brings her to the edge of death and, after a protracted struggle, immigration to Canada. It is an important story, but one requiring much adult guidance, even for an older age group than the 9-to-12 bracket for which it is recommended.

Many Wiebenga on Cambridge Record wrote:

Making Bombs for Hitler, by Marsha Forchuk Skrypuch (Scholastic Canada, 160 pages, $8.99 softcover) — How are parents or teachers supposed to teach children or pre-teens — or even teenagers — about the horrors of the Holocaust?

The only possible answer is that it must be done with great care and sensitivity.

Brantford writer Marsha Skrypuch, author of 15 books, delivers the truth about the Holocaust, describing it through the eyes of 12-year-old Lida, a Ukrainian girl who is forced into slave labour in Germany during the Second World War. Lida is honest, caring, and confused — why, she wonders, is all of this happening to her and to the people she loves?

I was surprised by the ways in which I was entranced by this book. As the reader, you want to know what’s going to happen to Lida and you are horrified alongside her when something awful happens, which is an all-too-common occurrence.

Making Bombs for Hitler does an incredible job of recounting the hateful acts committed against Jews and other “undesirables” during the war. It is a safe and sensitive book, as well as a great conversation starter, allowing for more than a few teachable moments with young people who read it.

For ages 9 to 12.

Gabriele Goldstone on Gabe’s Meanderings wrote:

The book begins with “… and the light was so white that it made my eyes ache.” This story makes my heart ache. At times I had to put it aside because of its intensity. The author shines a harsh light on more victims of the Nazi regime and makes me squirm with discomfort. Compelling read. Companion novel to Stolen Child. Both books should be read by anyone studying WWII because it wasn’t only Jewish children who suffered. That war was beyond awful. Kudos to Marsh Skrypuch for remembering the OST Arbeiter children.

Ukrainian Canadia on http://www.ukrcdn.com/2012/03/07/book-review-making-bombs-for-hitler/ wrote:

Making Bombs for Hitler begins in the aftermath of raids of Ukrainians kidnapped and transported to Nazi Germany as slave labour, known as Ostarbeiters. The main character Lida is separated from her sister Larissa and tries to survive the camp system with a keen intuition and quick wits, constantly in fear of what the fate or herself, her fellow children or her missing sister will be.

Lida is given quick wisdom in passing from a fellow slave labourer to ‘find a way to be useful, or they’ll kill you’. Lying about her young age and revealing a talent for embroidery taught by her mother (who was killed by the Nazis, while her father was killed by the Soviets) aids her in securing work in the laundry, avoiding the tragic fate of some of her companions who work in terrible conditions and regarded as sub-human. Her hard work ethic is noticed, and the few privileges it gains her shocks her German task masters as she selflessly shares them with her fellow slaves to help their deplorable conditions. As her reputation for quality and detail builds, Lida finds herself promoted to assembling weapons of destruction for the Nazis. This weighs heavily on her conscious, as she is haunted by the dilemma that her diligent work that keeps her useful (and therefore alive) contributes to stopping the people trying to liberate her.

Making Bombs for Hitler is a companion novel to Stolen Child which is centered around the story of Lida’s sister Larissa, whom are quickly separated at the beginning in this story.

I found this book to be quite enjoyable. While it boasts 170 pages, it is broken down into many digestible chapters and is written in a quick tempo that makes the book a surprisingly quick read. What is also refreshing is that the book does not go into too many details about World War 2, sparing the reader from all the names and places that could have turned the story into a boring history text. And while the book does bring into light the often overlooked plight of Ukrainians and even other nationalities (like the Poles or the Hungarians), one does not need to be too familiar with their back stories to understand their issues in this book.