Based on true events, a compelling story of love and hope published on the 100th anniversary of World War I. .

Ali and his fiancée Zeynep dream about leaving their home in Anatolia and building a new life together in Canada. But their homeland is controlled by the Turkish government, which is on the brink of war with Britain and Russia. And although Ali finds passage to Canada to work, he is forced to leave Zeynep behind until he can earn enough to bring her out to join him.

Ali and his fiancée Zeynep dream about leaving their home in Anatolia and building a new life together in Canada. But their homeland is controlled by the Turkish government, which is on the brink of war with Britain and Russia. And although Ali finds passage to Canada to work, he is forced to leave Zeynep behind until he can earn enough to bring her out to join him.

When the First World War breaks out and Canada joins Britain, Ali is declared an enemy alien. Unable to convince his captors that he is a refugee from an oppressive regime, he is thrown in an internment camp where he must count himself lucky to have a roof over his head and food to eat.

Meanwhile, Zeynep is a horrified witness to the suffering of her Christian Armenian neighbours under the Young Turk revolutionary forces. Caught in a country that is destroying its own people, she is determined to save a precious few. But if her plan succeeds, will Zeynep still find a way to cross the ocean to search out Ali? And if she does, will he still be waiting for her?

Excerpt:

Prologue

Eyolmez, Anatolia, June 1, 1913

Zeynep stood before me, her head tilted in concern. “What’s the matter?”

I hesitated as I stared at the dimple on Zeynep’s cheek, at her messy hair tied loosely in a piece of red silk. The thought of leaving her was almost more than I could bear.

“You know that Hagop Gregorian’s taking my brother with him when he travels back to Canada tomorrow. Well, it won’t just be Yousef going; Hagop is taking me too.”

She gasped.

“Hagop’s nephew Krikor was supposed to go, but you know he is sick,” I said quickly. “It would have been a waste of an expensive ticket if someone didn’t fill his place. Mama convinced Hagop to take me instead.”

A wave of anger passed over Zeynep’s face. “You promised we’d go together.”

“How many years would it take us to save up for two tickets?” I asked. “Mama convinced Hagop to giveme this ticket. Now I can go, take the job Hagop found for Krikor, and earn enough money for Mama’s taxes and your ticket. It will be faster this way.”

“But it’s not—,” began Zeynep.

Then she stopped. She knew I was right. No one bought our rugs or silk anymore. Our mountain pastures and patchy fields produced barely enough to feed us. It was impossible to make money here. The only people getting fat were the tax collectors.

The men took turns working in another country for a few years—sometimes even decades—and sent their earnings home. The women could then pay the taxes and buy food for the children, but it was a lonely existence for everyone. When the men came back years later, sometimes they didn’t recognize their own family. Some of the men never returned. That’s why Zeynep and I had decided to leave for Canada together. But for all our planning, we hadn’t managed to save any money.

Suddenly, with Krikor’s illness, everything was changed. Hagop had a rooming house in Canada. There was a good foundry job waiting for me. The freedom that loomed in front of me both frightened and excited me. Why couldn’t Zeynep be happy for me—for us?

“We may have nicer houses, but with the men all gone, the heart of this village is dead,” said Zeynep.

“I’ll come back for you as soon as I save the money. We’ll get married. In the meantime, I’ve brought you a gift.” I reached into my bag and drew out two identical journals. “One of these is for you. While we are apart, keep this journal for me and I’ll write in the other for you. As you fill each page, tear it out and mail it to me. I’ll do the same. That way, we will still be together.”

Zeynep took the journal and frowned, flipping through its blank pages. “I refuse to be your betrothed, never knowing when, or even if, you’ll come back.”

She pulled a thin leather strap from around her neck. Strung on it was her cherished blue evil-eye bead that had protected her ever since she was a baby. “Take this.” She stood on her tiptoes to put it over my head. “It will keep you from harm. I’ll always love you, but I will not wait for you. We both deserve better than that.”

She turned and walked away.

Zeynep’s betrayal shook me to the core. How would I live with the other half of me gone?

Reviews:on Smithsonian Book Dragon:

The year is 1913. Zeynap and Ali are teenage lovers in Anatolia (once Asia Minor, now modern Turkey) who part with a lingering sense of bitterness: Ali’s impending departure breaks their promise of escaping their village together. Feeling betrayed, Zeynap turns away: “I refuse to be your betrothed, never knowing when, or even if, you’ll come back.”

Ali will not give up hope of reunion: before he leaves, Ali presents Zeynap with identical journals: “While we are apart, keep this journal for me and I’ll write in the other for you … That way, we will still be together.” In return, Zeynap places her blue evil-eye bead over his head, a cherished momentum that has kept her safe since she was a baby. “I’ll always love you, but I will not wait for you,” she adds.

The Great War arrives in 1914, further separating the lovers. In Canada, Ali is sent to a prison camp for enemy aliens; Canada and Turkey are on opposite sides of the conflagration, and Anatolia is claimed by Turkey. At home in Anatolia, Zeynap bears witnesses to the genocide that obliterates over a million Armenian lives; her humanity and ingenuity make her an unlikely hero; her journal intended for Ali becomes a historical document of international importance.

Although the story is fictional, “it is based on real historical events,” award-winning Canadian author Marsha Forchuk Skrypuch writes in her ending “Author’s Note.” What happens to the lovers, their families, their homeland, demands and deserves far more attention. Both Zeynap and Ali are Alevi Kurds, an ethnic minority about which is little known in the West. They are Kurdish, not Turkish; they are not Muslim, they are Alevi, “a 6,000 year-old religion that originated in Anatolia. Over the centuries Alevism has incorporated aspects of other religions,” Skrypuch explains.

Already the author of five titles “set during the Armenian Genocide,” Skrypuch elucidates how “in all that writing and research, [she] completely missed an outstanding instance of bravery: the rescue of 40,000 Armenians by the Alevi Kurds of the Dersim Mountains.” Five years earlier, Skrypuch learned about a hundred “enemy aliens” living in her hometown of Brantford, Ontario, who were rounded up in the middle of the night on false charges, jailed, and sent to prison camps.

“These men were victims of shameful wartime hysteria directed at foreigners, yet they had come to Canada because of its reputation for freedom and tolerance.” Listed as Turkish, the men turned out to be Alevi Kurds. And so Skrypuch’s Dance began. The result is an eye-opening, significant literary and historical gift to readers, young and old.

Lisa Doucet on Canadian Children’s Book News wrote:

“It is June 1913, when Ali breaks the news to his fiancée Zeynep that he will be leaving their Anatolian village to go to Canada. Once there, he hopes to finally be able to save enough money to pay for her passage, and to build a new life for them there. But the world is on the brink of war and everything soon changes. The two record the events that they both witness in journal entries to each other, even though they both fear that they will never see one another again.

Alternating between these two sets of journal entries, readers learn Zeynep’s story of going to live and work with Christian missionaries. As World War I looms, she witnesses first-hand the horrors of the Armenian genocide at the hands of the Young Turks who now control the government. Conditions for her and the other Alevi Kurds are only marginally better, but that is small consolation as she watches Armenian men, women and children being cruelly treated and marched to their deaths. Meanwhile, in Canada, Ali and the other Alevi Kurds who had tried to settle in Brantford, Ontario, are falsely accused of a crime and sent to an internment camp in northern Ontario. As these two separate stories unfold, a vivid and devastating picture unfolds.

This latest work is an outstanding testament to Skrypuch’s mastery as a writer of historical fiction for young readers. She has created forthright and dramatic accounts of two little-known events from that time period, inviting readers of all ages to try to understand the depth of suffering that these groups have experienced. She has put a profoundly human face on the horrors of war while also creating an insightful portrait of the Alevi Kurds. Zeynep and Ali are both forced to mature very quickly, and their development is convincing. Skrypuch skillfully captures their voices, their longing, their heartbreak and their courage.”

Helen Norrie on Winnipeg Free Press wrote:

Brantford, Ont. author Marsha Forchuk Skrypuch has written a number of books about the Armenian genocide. Dance of the Banished (Pajama Press, 240 pages, $16, paperback) is set just before and during the First World War. It tells the story of two young lovers, Ali and Zetnep, separated by the war — Ali is taken to Canada by an uncle, while Zetnep remains in Anatolia. When war breaks out, Ali is imprisoned in an internment camp as an enemy alien, while Zetnep struggles to survive in a place where neighbours and friends are being massacred as Armenian Christians — and only an acquaintance with the American consul prevents her from being arrested.

The scenes in the internment camp are some of the most interesting parts of Skrypuch’s story, as Ali is forced to cut down trees, which he regards as sacred, in order to construct buildings for the camp. Skrypuch has just been appointed to Canada’s First World War Internment Recognition Endowment Council as a direct descendent of an internee. Written for ages 12 and up.

Vikki Terrile on VOYA wrote:

4Q 3P J S

Skrypuch, Marsha Forchuk. Dance of the Banished. Pajama Press, 2015. 288p. $15.95

Trade pb. 978-1-927485-65-1.

In 1913 Anatolia, Ali leaves his fiancée, Zeynep, to start their planned new life in

Canada, with the expectation he will be able to send for her soon. But when World War I

begins, Ali finds himself in an internment camp and Zeynep in the midst of the Armenian

Genocide. Will they find their way back to each other before their worlds are torn apart?

Canadian author Skrypuch, who has written several other well-received historical novels

about World War I and the Armenian Genocide, has created an absorbing glimpse into

a dark period in world history and the human consequences of war. Most of the novel

is told through letters that Zeynep writes (but does not send) to Ali; as she becomes

involved in protecting the Armenian people, these letters become an eye-witness account

to the atrocities being committed against them. Ali, picked up as a Turk enemy alien (he

and Zeynep are actually Alevi Kurds) and sent to the Kapuskasing prison internment

camp, tells less of the story, including a subplot about his involvement with a young Cree

woman who wants to become a nurse.

There is not much distinction between the narrative voices of the two main

characters, but there is still so much humanity in the writing and the story, no one will

mind. The history comes alive, particularly in Zeynep’s chapters, and fans of historical

or war novels, who may not know much about the Canadian internment camps or the

Armenian Genocide, will surely be engaged enough to do further research (this reviewer

did).—Vikki Terrile.

on Kirkus:

“An eye-opening exposé of historical outrages committed in two countries, with intriguing glimpses of a minority group that is not well-known in the Americas.”

World War I separates a betrothed Anatolian couple—leaving one to witness the Armenian genocide and sending the other to a prison camp…in Canada.

Cast as letters and journal entries, the double narrative records the experiences of Zeynep, a villager transplanted to the “mighty city of Harput,” and Ali, who is swept up with other supposed enemy aliens and shipped to a remote camp in central Ontario before he can send for Zeynep. Neither is of Turkish descent: They are Kurds practicing the ancient, indigenous Alevi faith. These distinctions make no difference to Canadian authorities in Ali’s case, but they do give Zeynep some protection as she records a rising tide of atrocities committed against her Armenian (Christian) friends and neighbors. The characters often come off as mouthpieces (“The minorities must stick together or we’re all dead”), and the brief insertion of a young Cree woman into the cast so that she and Ali can compare lifestyles and religious beliefs is an awkward interpolation. Nevertheless, both parts of the author’s tale being based on actual incidents, readers may come away with enhanced awareness of the multiplicity of smaller ethnic groups, both in other countries and their own.

An eye-opening exposé of historical outrages committed in two countries, with intriguing glimpses of a minority group that is not well-known in the Americas. (afterword) (Historical fiction. 11-14)

Barbra Hesson on Calgary Public Library wrote:

Based on true events, this story takes place in Anatolia and Canada in 1914, during the breakout of First World War. When Ali moves to Canada to secure a better life for himself and Zeynep, they communicate by journals. It’s a love story filled with tragedy when Ali is forced into a Canadian internment camp, and Zeynep faces horrors as the Ottoman Army marches through her villages. This moving book will enlighten and appeal to readers ages 12 to adult.—Barbra Hesson, Calgary Herald, Nov 1, 2014.

Joanne Peters on CM wrote:

War has a way of changing people’s plans. Dance of the Banished begins in 1913, the year before the outbreak of World War I. Zeynep and Ali live in Eyolmez, Anatolia, a region now part of the modern country of Turkey. However, they are not Turks; they are Alevi Kurds, practicing an ancient religion which incorporated elements of Islam, Christianity, and animism, and speakers of the language, Zaza. Also living in Anatolia are ethnic Armenians, believed, by some scholars, to be distantly related to the Alevi Kurds: “the distance between Alevis and Armenians is no thicker than the membrane of an onion.” (p. 229) Predominantly Christian, the Armenians are enemies of the Ottoman Empire.

In Part One of the novel, Ali leaves Zeynep with a journal; in it, she will write letters to be sent to him in Canada. He will do the same for her, and the book is told through both narration and their largely unreceived letters to each other. Zeynep is angry at Ali’s desertion, and when her future mother-in-law finds an opportunity to make her an object of derision in their village community, Zeynep decides that, like Ali, “it’s time for [her] to figure out [her] own escape.” (p. 13) Her chance arrives in the form of American Protestant missionaries who are on their way to the hillside city of Harput where they run a school for orphans. Able to read and write, as well as being fluent in Armenian, Zeynep wants to work at the school, but a decidedly un-Christian missionary named Miss Anton rejects her because Zeynep is unwilling to give up the “false gods” of the Alevi faith. Undeterred, Zeynep leaves home in the dead of night and steals aboard the missionaries’ wagon, arriving in Harput in the spring of 1914, months before World War I begins. Harput is just over the border from Russia, a long-standing enemy of Germany, and Turkey has been a long-standing ally of Germany. Turkey has been wracked by years of war in the Balkans, but it is certain that Turkey will enter this conflict, too. It is clear to Zeynep that, although she has temporarily escaped the horrors of the Young Turkish Revolutionary army that “is like a cloud of locusts, destroying everything in its path”, (p. 46), her family members back in Eyolmez are in grave danger. Months later, Zeynep’s Aunt Besee, Cousin Fatma, and Fatma’s son arrive at the mission in Harput and give a full account of the invasion of their town: “they took over the entire village – both the Armenian and Alevi quarters – kicking people out of their own homes. The soldiers took everything.” (p. 50) Most frightening of all, they took the Armenians, and no one seems to know where. Only one consolation exists, a letter from Ali, who is working in an iron foundry in Brantford, ON, saving his money, faithful in his love for her.

Part Two of the book moves across the ocean, to Canada. World War I has made life difficult for immigrants from those countries now at war with Canada (Germans, Ukrainians and other Slavic peoples believed to “Austrian”, and anyone who came from the Ottoman Empire). Ali, his brother, and 98 other Alevis are imprisoned, having been rounded up on false charges of planning to bomb Brantford’s post office building. Confusion as to the Alevi Kurds’ nationality (anyone who comes from Turkey must be a Turk, and, therefore, an enemy) leads to their being sent to an internment camp in Kapuskasing, ON, where their personal belongings are confiscated and burned, and the prisoners clear trees in the wilderness, building their own bunkhouses, enduring lives of incredible deprivation, and, of course, the paralyzing cold of the Canadian frontier.

The eight-part novel then alternates in the telling of Zeynep and Ali’s stories during those terrible years of the First World War. Zeynep suffers influenza, typhus, and continual fear for her family and her Armenian friends. The Armenians are starved, tortured, their homes vandalized and looted, rounded up and “marched . . . out into the desert to die” (p. 198) Zeynep becomes desperate in her attempt to save her Armenian Christian friends and that becomes her life’s mission, even as she lives in hope of a reunion with her fiancé. As for Ali, life at camp is a “backbreaking and soul breaking” (p. 105) round of cutting down trees and building bunkhouses for more prisoners. Challenging the guards earns him a trip to Prison Island where a week of isolation can drive a person mad. Fortunately for him, the help of a pretty young Cree trapper ensures that he survives the ordeal, and although Ali is tempted to leave with Nadie and live with her people, he knows that escaping the camp will deny him any hope of becoming a Canadian citizen, and thus, the chance to bring Zeynep to Canada.

In Dance of the Banished, Marsha Forchuk Skrypuch continues to explore the plight of those to whom she dedicates the book: “for the forgotten ones.” Ali and Zeynep are ordinary people whose lives are torn apart by the extraordinary complexities of international politics. The stories and struggles of thousands like them are often forgotten over the course of time. Although the novel is fiction, it is based on two significant events of World War I: Canada’s establishment of 24 internment camps in which both immigrants and the Canadian-born were held as “enemy aliens” and forced to do heavy labour, and the Armenian genocide of 1915 which resulted in the death of more than one million Armenians. Furthermore, Skrypuch lives in Brantford, and when two local historians presented her with newspaper clippings detailing the round-up of “enemy aliens”, she was intrigued, not the least because she is, herself, the granddaughter of a Ukrainian immigrant who was interned in a camp in Jasper, AB. She wondered, “What must it have been like for those 100 men from Brantford?” knowing the degree to which it affected her grandfather.

The inside covers contain maps detailing the geography of both Zeynep and Ali’s stories, and the “Author’s Note” provides considerable background on the Alevi Kurds; both offer a better sense of the journeys undertaken by both main characters and of their cultural context. Although the novel’s press release suggests that its intended audience is 12+, I think that it’s really a story for somewhat older readers. As the story opens, Ali and Zeynep are teenagers, but, by its end, their life experiences have matured them far beyond their years. Their “letters” are rich in detail, perhaps more typical of a time when communication wasn’t instant. The author does an excellent job of describing the hardships faced by both, including Zeynep’s culture shock when living with the American missionaries and Ali’s attempts to maintain his dignity in the face of the unwarranted cruelty of the camp guards. I am not certain that the inclusion of the character of Nadie, the Cree trapper who helps Ali to stay alive and sane during his time on Prison Island, was necessary. Yes, she was necessary to provide a reason for Ali’s being sent to Prison Island, her culture has a similar view of nature as do the Alevi Kurds, and she is certainly a temptation to Ali’s promise to be true to Zeynep, but, at times, her presence in the story seemed to be almost a distraction.

However, this a minor issue in an otherwise very strong story. Dance of the Banished is definitely a worthwhile acquisition for middle and high school library collections; it will complement other works focusing on the story of young people affected by war-time, including The Diary of Anne Frank, provide a very accessible perspective on life in one of Canada’s First World War Internment Camps, as well as introducing readers to the story of the Armenian genocide, an event with which many young Canadians might not be familiar.

Highly Recommended.

A retired teacher-librarian, Joanne Peters lives in Winnipeg, MB.

on Kirkus:

“An eye-opening exposé of historical outrages committed in two countries, with intriguing glimpses of a minority group that is not well-known in the Americas.”

World War I separates a betrothed Anatolian couple—leaving one to witness the Armenian genocide and sending the other to a prison camp…in Canada.

Cast as letters and journal entries, the double narrative records the experiences of Zeynep, a villager transplanted to the “mighty city of Harput,” and Ali, who is swept up with other supposed enemy aliens and shipped to a remote camp in central Ontario before he can send for Zeynep. Neither is of Turkish descent: They are Kurds practicing the ancient, indigenous Alevi faith. These distinctions make no difference to Canadian authorities in Ali’s case, but they do give Zeynep some protection as she records a rising tide of atrocities committed against her Armenian (Christian) friends and neighbors. The characters often come off as mouthpieces (“The minorities must stick together or we’re all dead”), and the brief insertion of a young Cree woman into the cast so that she and Ali can compare lifestyles and religious beliefs is an awkward interpolation. Nevertheless, both parts of the author’s tale being based on actual incidents, readers may come away with enhanced awareness of the multiplicity of smaller ethnic groups, both in other countries and their own.

An eye-opening exposé of historical outrages committed in two countries, with intriguing glimpses of a minority group that is not well-known in the Americas. (afterword) (Historical fiction. 11-14)

on Ex Libris Notes:

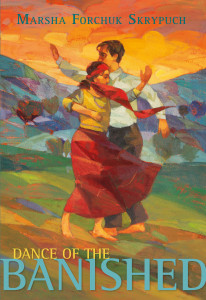

“Dance of the Banished is a beautifully crafted novel, from its gorgeous cover inviting readers into its pages, to the well-told story of two lovers separated by distance and war. Using alternating narratives, Skrypuch effectively presents the effects of war in two very different countries.”

“The author’s extensive research on the Armenian genocide is evident in Dance of the Banished. Her development of the setting of the novel is realistic and her characters believable for this time period and for the Alevi culture she portrays so well. ”

“Dance of the Banished is an excellent piece of historical fiction and Marsha Forchuk Skrypuch’s best work to date. Definitely a future White Pine Award winner for this increasingly popular and talented Canadian children’s author. ”

on National Reading Campaign:

In Dance of the Banished, acclaimed author, Marsha Skrypuch, once again breathes life into a piece of history with passionate clarity. Published on the one hundredth anniversary of World War I, Dance of the Banished tells the dual stories of alien internment in Canada and the Armenian Genocide in Turkey, both from an unusual perspective.Zeynap, fierce and bold, and Ali, caring and principled, live in the same village in Anatolia and plan to marry. Unexpectedly, Ali is sent to Canada and Zeynap is left behind. Each writes in a journal for the other, but as war comes to both countries it is unlikely their words will ever be shared. Still, they keep on. Zeynap writes an eyewitness account of the genocide from the point of view of the Alevi Kurds, telling a little known side of this tragic story. Ali, in turn, gives an accounting of life in an internment camp in, surprisingly, Kapuskasing. For each, the journal entries are a coping mechanism, a way to bear witness to the atrocities of war and ultimately, to bring justice.Skrypuch’s compelling characters give an authentic voice to this well researched story. It is definitely a book for adults as well as teens. And although it is a story of war it includes moments of great joy, making it much more than a tragedy. Whether together in Turkey or alone in banishment, both Zeynap and Ali are able to lose themselves when they dance. Their troubles are momentarily forgotten in an ecstasy of whirling that reminds us of the cyclical nature of human events. Preserving the past, as Skrypuch does so well, is part of that cycle.Penny Draper lives in Victoria, British Columbia. She is the author of the award-winning “Disaster Strikes!” series, historical fiction that places young protagonists at the centre of real Canadian disasters.Logo-NoTypeThe National Reading Campaign publishes children’s book reviews under a Creative Commons License. This review is entirely free to reproduce and republish online and in print. Credit must be given to the reviewer and the National Reading Campaign. Reviews can be edited for brevity only. Contact Us for more information.

on Quill & Quire:

From Quill & Quire: Dance of the Banished will appeal strongly to kids with an interest in the past, even those a couple of grades younger than the recommended reading level. It is a timely contribution to both Canadian and global First World War history.

Helen Kubiw on Canlit for Little Canadians wrote:

Dance of the Banished is an old tale. It’s the familiar love story in which two young people are separated, here by family, distance and war. But, sadly, it’s also the story of prejudice, fear, and injustice, and the subsequent torment that intensifies that separation. Dance of the Banished may be an old story in its foundations, but its context is wholly unique, expertly researched and penned by award-winning author Marsha Forchuk Skrypuch.

Our story begins in 1913 Anatolia (now essentially the republic of Turkey), a nation of Christians, Muslims and Alevis, an ancient group with a unique Islamist belief system. When Ali, a young Alevi Kurd, unexpectedly immigrates to Canada with his married brother Yousef, he leaves behind his betrothed, Zeynep, another Alevi Kurd, giving her a notebook in which to write him until they are together again. Having planned to go together once they’d saved enough money, Zeynep knows Ali’s mother has orchestrated this separation, and refuses to wait for him, though she gifts him with her blue evil eye necklace to keep him safe.

Though both Ali and Zeynep record their experiences in their matching notebooks, providing the basis for this book, neither is communicating directly with the other. In fact, hearing nothing from Ali and no longer feeling a part of her community, Zeynep follows visiting Protestant missionaries to the city of Harput, hopeful of improving her lot in life, including getting an education. Though the lifestyles of the Christian North Americans and Armenians in their Western clothing and the Turkish Muslims differ significantly from her own, Zeynep appreciates this diversity, learning and helping the Reverend John Emmonds and his wife Lenore at the hospital and at their simple home.

With much strife in Europe at the beginning of 1914, the Ottoman army is becoming more oppressive to the Alevis and the Armenians, raiding villages, taking whatever they choose, and finally, when Austria-Hungary and Germany declare war on Russia, threatening death to those who attempt to escape the draft or those who help them. Within a few months, the Alevis are starving, and the Armenians are being murdered en masse. Zeynep watches and listens, documenting all she witnesses in her notebook; in fact, she begins recording everything for the American Consul, Leslie Davis, who plays a significant role in saving the lives of many.

Meanwhile, with the declaration of war in 1914, Ali and Yousef, like all foreigners, are let go from their jobs in Brantford Ontario. Rounded up as Turkish “enemy aliens”, Ali and Yousef, along with many others, are shipped to the wilderness of Kapuskasing. Still in a minority, the Alevis are forced to cut majestic trees, contrary to Alevism, and endure the never-ending discrimination, even within the camp.

On different sides of the world, Zeynep and Ali continue to honour their beliefs and heritage, though choosing to think beyond themselves, all the while wondering about the other, their safety and potential for reunion.

Spotlighting little known historical injustices has become a trademark for Marsha Forchuk Skrypuch, her desire to enlighten and disclose indicative of her own integrity and search for equity. From the Armenian genocide (The Hunger, 2001; Nobody’s Child, 2003; Daughter of War, 2008), to the Ukrainian Holodomyr (Enough, 2004), the treatment of Ukrainians during World War II (Stolen Child, 2010; Making Bombs for Hitler, 2012; Underground Soldier, 2014) and the Vietnamese War orphans (Last Airlift, 2012; One Step at a Time, 2013), Marsha Skrypuch ensures that transgressions, even atrocities, from our histories are not forgotten.

By creating legitimate characters in her fiction who bring varied and personal perspectives to the situations experienced and who speak through their questions and confusions and convictions, Marsha Skrypuch can tell the whole story, not just the public one. In Dance of the Banished, we listen to Alevi Kurds and Armenians in both Canada and Anatolia, to those with family and those without, to the Turks shamed by the actions of their government and those complicit in the horrors, to Canadians who stood guard at internment camps and those who recognized the discrimination for what it was. Consequently, her readers submit to understanding the big picture, not necessarily the pretty, sanitized one. And we are grateful for that opportunity and bold honesty.

Dance of the Banished reveals truths from Canada and Asia Minor that some may prefer to leave forgotten or hidden, but Marsha Skrypuch‘s words and heart tell us that we can trust her to tell it right and well, as she does so eloquently here and always.

Urve Tamburg wrote:

Dance of the Banished is an evocative title suggesting a novel about exile, punishment, and isolation. But it is also a love story about two Alevi Kurd young people separated by war, and isolated from their culture. Divided by an ocean, Ali and Zeynep long to be together. Their dreams are similar to those of any young couple. They desire the freedom to make a safe home for themselves, and to practice their religion, and honour their culture without fear of persecution.

Meticulously researched and sensitively written by award-winning author Marsha Forchuk Skrypuch, Ali and Zeynep take us on their journey that begins in the months prior to World War 1.

In 1913 Anatolia, a young couple, Ali and Zeynep, dream of building a new life in Canada together. But when Ali suddenly finds passage to Canada for his brother and himself, he must leave his fiancée, Zeynep, behind. He promises to send for her when he has earned enough money for her passage. Zeynep, angry at being left behind, tells Ali she refuses to wait for him, but before he leaves, she gives him an evil eye necklace for protection. Ali presents Zeynep a journal to write in, encouraging her to record her life and thoughts until they can be together again. He has a matching journal, and promises to do the same.

It is through the diaries of Ali and Zeynep that the story is told. Through their writing in their journals, each tells the other about their experiences and thoughts.

Through Zeynep’s journal, we learn about her frustration and disappointment when Ali breaks his promise and leaves her behind. And to make matters worse, she suspects Ali’s mother orchestrated his sudden departure. But Zeynep refuses to give up her dream of finding better opportunities, and follows visiting Christian missionaries to a nearby city in hopes of improving her life and obtaining an education. Zeynep’s observations about Western customs give us insight into the Alevi culture. For example, she puzzles that the house has many rooms, and separate rooms for people to sleep in and that one room is used for eating only when company come to visit. Zeynep quickly becomes accustomed to her new surroundings, and helps the missionaries at the hospital.

Soon, Europe is on the brink of World War 1, and the Ottoman Army marches through village after village in Anatolia, leaving behind destruction and death. Zeynep is horrified when the Young Turks start to kill people who are non-Turks, specifically the Alevis and the Armenians. Young men are forced into the army, and non-compliance with conscription means death. Zeynep realizes that Ali is safer in Canada. Alevis and Armenians fear for their lives, and escape into the mountains enduring cold and thirst and starvation.

With the encouragement of the American consul, Leslie Davis, she becomes an important eyewitness to these events since she is a non-Christian. He encourages Zeynep to continue to write in Zaza, and even provides her with special thick paper, and a selection of pens.

On the other side of the ocean, Canada is at war with the Ottoman Empire, Germany and Austria. Ali has found a job in Brantford, Ontario, but when World War I erupts, all foreigners are let go for “patriotic reasons.” Ali futilely tries to explain that he is an Alevi Kurd, and no friend of the Turks. But everyone assumes because he is from Turkey, he is a Turk. Ali and his brother are sent away to Kapuskasing, Ontario to work in a internment camp cutting down trees, an act which causes Ali much grief since felling trees is forbidden in the Alevi religion.

In their separate journals, Zeynep and Ali both express a desire to dance the semah with each other again. We feel their longing to perform the ritual Alevi dance-prayer which is danced by six couples, both men and women, side by side. Ali pictures Zeynep’s red head scarf swirling, and Zeynep yearns to be with Ali again. The memory of their last dance together sustains them both as they ponder their choices in virtually hopeless situations.

Through the diaries of Ali and Zeynep, we experience the horrors of war, the injustice of exile, and their love for each other and their culture. They seek a better life, but are thwarted by the outbreak of war, and circumstances where they are forced to fight for their lives, their love, and their culture. How will Zeynep get to Canada when it is at war with Turkey?

The dedication for Dance of the Banished reads “For the forgotten ones.” In her nineteenth book, Marsha Forchuk Skrypuch again gives a revealing and compassionate voice to an under-represented group of people, and shines a light on little-known events in history. Writing about historical injustices for young adults requires a solid grip of the events, sensitivity, and the ability to juggle multiple perspectives in order to create a compelling story that not only keeps us turning the pages, but also brings forward truths that may have been forgotten or buried. Dance of the Banished enlightens us about the plight of the Alevi Kurds during World War 1, saddens us as we find out about the massacre of the Armenians, and maybe even embarrasses us as we discover how “foreigners” were treated in Ontario. Her characters are human, and multifaceted, and make us think about how we would react in times of great stress if our homeland, families, or loved ones were in danger. The answers are never easy, and Marsha does not shy away from difficult and heart-wrenching choices.

Marsha has received numerous awards and honours for her picture books and young adult novels, including a nomination for the Canadian Library Association Book of the Year in 2007. Marsha has penned the bestselling Dear Canada book, Prisoners in the Promised Land. She has written about the Ukrainian Holodomyr, the Armenian genocide, and the Vietnamese war orphans (One Step at a Time, The Last Airlift). Her most recent books are about Ukrainians in World War II (Underground Soldier, Making Bombs for Hitler, Stolen Child).

Recommended for ages 12 and up.

on A Year Of Books:

Following the launch of this terrific book last week (see post below), I devoured it as we relaxed beneath the trees on a campsite at the Pinery. Similar to this author’s previous novels, this story wove together history and a compelling story of injustice, hope and tenacity to survive in terrible conditions. This book also had a Brantford connection, which is a treat to read!

This novel, Forchuk Skrypuch’s fifth book about the Armenian genocide, alternates between Ali and Zeynep who are writing in journals to each other during their separation. Ali leaves Anatolia to find a better life in Canada, settling in Brantford and working in a foundry. He ends up placed in an internment camp in Northern Ontario after being identified as the very people he was fleeing from. Zeynep remains behind waiting to join him, living with missionaries and helping at the hospital. During this time, the Young Turks were working to extinguish the Christian Armenians by killing the men and forcing the women and children to march through the desert, starving to their deaths. Zeynep continues to write in her journal, writing at the American consulate office, as the importance of her journal and the documentation of these terrible crimes has been recognized.

Both Ali and Zeynep show incredible bravery and compassion as they help others avoid persecution. The author shared that while the book is fiction, “every single thing in my book happened”. This book is important to read and as Zeynep says,

“what I have witnessed is evidence of a terrible crime and the world must know about it, because, he says, that what we forget, we are bound to repeat”.

Part action novel, part history, part love story – Dance of the Banished is a book which will linger in the reader’s mind.

Zeynep and Ali are young Alevi Kurds in Anatolia, Turkey who are dreaming of a future together. Ali leaves his fiancée when he gets passage to Canada and Zeynep’s world is thrown into chaos when war breaks out. Their ensuing stories are told in alternating chapters and letters. Zeynep travels to a city where life is becoming more dangerous each day. It soon becomes clear that the Turks are using the camouflage of war to murder the minority Armenian population and Zeynep is a horrified witness.

Meanwhile, in Brampton, Ontario Ali is swept up with other immigrants and imprisoned in a war camp in northern Ontario. To the Canadian government, he is Turkish because he came from Turkey, and is therefore an enemy of Canada. Through everything, the main couple hold each other in their hearts and dream of dancing the semah together again. The semah is a religious dance and form of worship for the Alexi Kurds and is the inspiration for the book’s title and the cover painting by Pascal Milelli.

There are many stories set during World War 1, however few have touched on the period of the Armenian genocide and few books have also tackled the uncomfortable truth about innocents interred in Canada’s wartime camps. The characters’ love for each other and fierce hope despite terrible odds is very compelling and urges an ending of reunion and the righting of wrongs.

There is a reason why this book won the Geoffrey Bilson Award for Historical Fiction. Marsha Forchuk Skrypuch can bring history to life in a way that few others can.

World of Words review. Excerpt:

A dynamic and compelling story with likeable and realistic characters, this fictionalized narrative about how war often makes no distinctions between cultural groups will appeal to middle and secondary readers interested in history, romance, and how political movements on an international scale often wreak havoc at the local and individual levels. A deeply engaging plot that addresses many of the nuances of World War I, this book will make a great companion to Sanders’ series, The Rachel Trilogy, as well as Between Shades of Gray (Ruta Sepetys, 2012), which also address the concepts of movement, transitions, and how politics disrupt individual lives.

Interview on Nash Holos here:

http://www.nashholos.com/vancouver-edition-august-17-2014/

School Libraries in Canada interview here:

//clatoolbox.ca/casl/slicv32n3/323skrypuch.html