Columns

By Marsha Forchuk Skrypuch

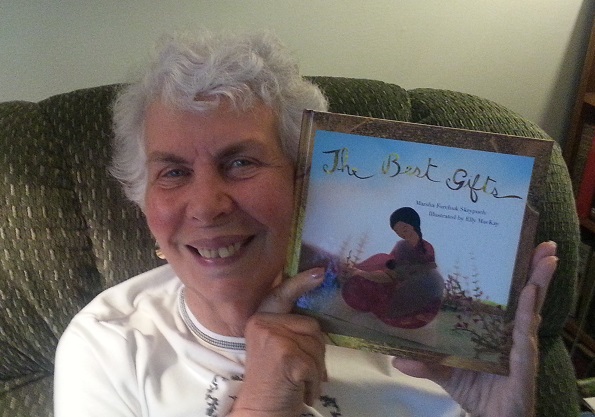

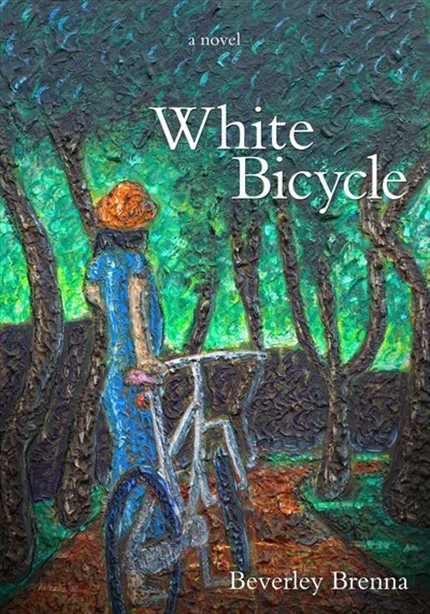

The painting that graces the cover of The White Bicycle was created by a critically acclaimed artist who was diagnosed with autism as a child. It is the kind of book cover that might be overlooked alongside flashier covers, and in that way it is emblematic of the story that it encloses.

The painting that graces the cover of The White Bicycle was created by a critically acclaimed artist who was diagnosed with autism as a child. It is the kind of book cover that might be overlooked alongside flashier covers, and in that way it is emblematic of the story that it encloses.

Taylor is a brilliant and autistic young woman whose unique gifts might be overlooked alongside other teens her age, but she is worth getting to know. Beverley Brenna nailed this remarkable teen’s voice. This book is nothing short of a tour de force. I urge you to read it. It is the third book in a trilogy, but it can be read on its own.

Taylor perceives the world differently from those around her, so things that are obvious to the reader are a mystery to Taylor. She has particular difficulty reading the emotions of those around her. It is fascinating to witness scenes from her point of view and to see how she interprets them.

But of course, in addition to being autistic, Taylor is a young woman longing for independence. She needed her mother for so very long, but now she finds that her mother intrudes.

Here is what Beverley Brenna had to say about the creation of this novel:

I especially appreciated seeing Taylor’s relationship with her parents, and in particular, her mother. How did you do that?

I did think a great deal about Taylor’s family context and I hoped that by showing scenes between her and her parents, we could learn more about her. I think about these scenes much as a playwright might think about character development—through dialogue. I also concentrated on getting Taylor’s individual relationship right with her mom, but at the same time, I did think about what from this relationship might many or most people relate to—what parts of it result from her autism and what parts of it result for her being a young person in the journey for independence from the person who most makes her feel dependent. In this way I hoped to create situations that were personal for Taylor, but at the same time possibly more universal to readers.

Can you tell me about how your mother has influenced your career as a writer?

My mother was a gifted poet and storyteller. I grew up saturated in rich literary forms, supported by both parents as readers, as well as the example my mother provided of writing for pleasure. I published my first poem in The Western Producer‘s Young Co-op pages, at age seven, and seeing my work in print was a tremendous motivation. My mother facilitated that entry because, in childhood, she herself had published poetry in a farm newspaper and knew the satisfaction, for a writer, of finding an audience. Some of her work can be found at lulu.com under the name Myra Stilborn, and she is probably best known for her sonnets. She passed away last year at age 95, and many of the family stories she had been fond of telling were with her until the end although her memory was fading that last year. She was also giving poetry readings at her seniors’ facility and, finally, in the care home, during the last months of her life. For her, poetry was a lens through which she attempted to know the world, and she was very fortunately able to see through that lens, with delight and clarity, throughout the long span of her life.

You have a gift for developing compelling characters who have learning needs. How do you to that? And why?

Thanks for the compliment! My experience as a teacher has gifted me, I think, with an understanding of diversity in terms of ability, and my knowledge of characters whose voices haven’t been heard often in work for young people, as well as my research interests as an academic, have united towards the characters you describe. In cataloguing Canadian children’s novels about characters who are differently abled, I discovered a number of patterns and trends in available work. One of these trends is that characters with disabilities rarely travel. In my work to extend the character of Taylor Jane as an authentic young woman with Asperger’s Syndrome, I have deliberately scaffolded opportunities for her to experience travel both locally and internationally, as a way to dislodge what I think is a negative stereotype. I was lucky in attending a conference in Miami two years ago where I met another Taylor, an artist named Taylor Crowe, who was the keynote speaker about growing up with autism. Meeting him was quite serendipitous, and since that time he has designed the cover for The White Bicycle, the last book in the Taylor Jane series.

The White Bicycle is a powerful read and a sophisticated narrative. Why did you decide to write it as a children’s/YA novel instead of an adult novel? Or did you decide?

I think that we have a lack of “crossover” title that suit both older kids and adults, and I perceive there to be a gap between the kind of “writing up” that’s done for kids, and then what happens when post-highschool age youth reach for literature. What’s available for this older age group, in terms of realistic fiction, tends to be about younger kids, or else adults, and in some ways I think authors may have forgotten about the transient population of readers between ages 17 or so and 21 where sometimes adolescent issues prevail at the same time that adult issues are introduced.

What was your biggest challenge in writing this book?

I was writing it at the time my beautiful 95 year old mother was slipping away, and the choice to create the character of Adelaide as a woman of a similar age was at times quite joyful, and at times painful. I did think hard about Adelaide’s transition from life to death and it wasn’t exactly a break from the experiences I was going through in real life with my mom. Adelaide is quite different from my mother in many ways, but some of their experiences are the same, and it was satisfying to be able to set some of these things into the world of fiction to honour my mother’s life and stories.

This is the third in a trilogy, but have you considered writing a 4th book about Taylor?

I’m happy to say that the written part of Taylor’s story is finished, and I was very sure of this when I wrapped up The White Bicycle with an ending that was semantically and syntactically parallel to the beginning of the series in Wild Orchid. If you go and read the first chapter of Wild Orchid, you will see the kind of dance that’s happening with the text as it concludes at the end of the trilogy. Hopefully readers will imagine Taylor Jane going forward into a rich an interesting life now that the series is finished.

I play with repetition in a few other places in the series. One such place is in Waiting for No One where there are two very carefully orchestrated chapters about Dance Class. I have internalized this kind of balance from Theatre of the Absurd, where repetition of scenes and dialogue is sometimes quite prominent.

What advice do you have to parents who wonder if their child may have a form of autism or other challenge?

There are different perspectives at work when the question of diagnoses arises. I have the belief that diagnostic information offers opportunity, and in terms of young people, a diagnosis can direct support teams–including parents and the young person, of course–towards looking for and finding useful strategies.

The fictional Taylor did find some relief once she received her diagnosis in grade five. Her supports were not always appropriate, however. In Wild Orchid she reminisces about taking medication as a child, provided in an attempt to control her behaviour, and this medication made her wish she was dead. Taylor criticizes the fact that this medication was never tested on kids. I wanted to come back to the topic of medication in Waiting for No One, because here Taylor struggles with obsessive compulsive disorder and she does find medication, and the support of a psychiatrist, helpful. Any support can be positive or negative depending on the individual and the situation, and the value of having a strong support team, including medical personnel, is that strategies can be tried, reviewed, and adapted, until the best possible support “recipe” is created so that people can function as best as is possible within the least restrictive environment.

It’s my understanding that families, who are sensitive to the idea of diagnoses, can keep any diagnoses private until they wish to share them if the diagnoses have been made by health care professionals outside the school system. If an educational psychologist has suggested something like a learning disability in a report paid for by a school division, that report can also be retained in a central office location, without appearing in a child’s cumulative school folder, at a parent’s written request–at least, this is the way it used to be in my experience in school divisions. Teachers, then, don’t have access to this report until the parent grants permission. In this way, a family can search for further information without necessarily deciding what to do with the end result of that search, until they are ready.

I have seen benefits to young people once school teams have been given diagnostic information about kids, especially where new strategies can be tried, and where extra support people can be hired through government funding. This was definitely a positive in Taylor’s case.

How many stories do you have in your head right now?

Too many to count. It’s end of term at the university and each day I think perhaps I’ll get a few lines done on one new project or another, but there’s a lot of marking to be done right now and so my other projects have to wait. Luckily the students here are exceptionally good, and I enjoy reading their work. My next publication is a book of poems called The Bug House Family Restaurant for ages 7 and up. It’s coming from Tradewind Books next spring, and is a collection of work about the prospect of eating bugs. Adults don’t tend to like my subject matter very much, but the kids I’ve so far shared with eat it up, if you know what I mean! “If ever you’ve been bugged by bugs, please don’t be so suspicious. With one good chef and half a chance…they might be quite delicious!”

What do you do when you’re not writing?

I slip out to Blackstrap Lake to kayak when I can, and in the winter, enjoy long walks. My husband and I are avid theatre goers and we enjoy music, as well. As a university faculty member, I am teaching preservice teachers, as well as graduate students, and I spend a lot of time in my office working with students, and teaching classes on campus. I’m also involved in various research projects related to children’s literature and reading comprehension, so part of my focus each day is on balance–when to do what,

and for how long. I could spend all of my time on any of these passion areas, and so it’s really a matter of balance.

What advice do you have for aspiring writers, beyond the usual “read read read, write write write?

Find other people who enjoy writing and who are willing to read and respond to your work. A “writers’ group” designed for providing feedback can be really helpful in offering positive encouragement as well as useful feedback towards revision. As good readers in the context of our own work, writers do not always see the things that outside responders can, and reading someone else’s work is a great way also to train ourselves as editors. I have a few more specific suggestions under the “Writers’ Advisory” tab on my website.

What did I forget to ask you, and what is the answer?

I’m interested in creating characters who are “differently abled” because I think the landscape of books for young people hasn’t included all the voices of real kids. I think we as adults need to be vigilant about this, and as parents, teachers and librarians… we need to keep seeking ways to offer kids safe and productive opportunities to think about self and other to promote understanding and respect for diversity. Books can help us shape the world, and in this way, change the world—one reader at a time.

The nominees for the 2014 Kobzar Literary Award, handed out every other year in recognition of Canadian books that present “a Ukrainian Canadian theme with literary merit,” include poetry, a play, a “folk history,” and a pair of novels (including one for kids). The shortlist is as follows:

The nominees for the 2014 Kobzar Literary Award, handed out every other year in recognition of Canadian books that present “a Ukrainian Canadian theme with literary merit,” include poetry, a play, a “folk history,” and a pair of novels (including one for kids). The shortlist is as follows: